Black Faeries Matter

A short exploration in softer depictions of Black fantasy tropes

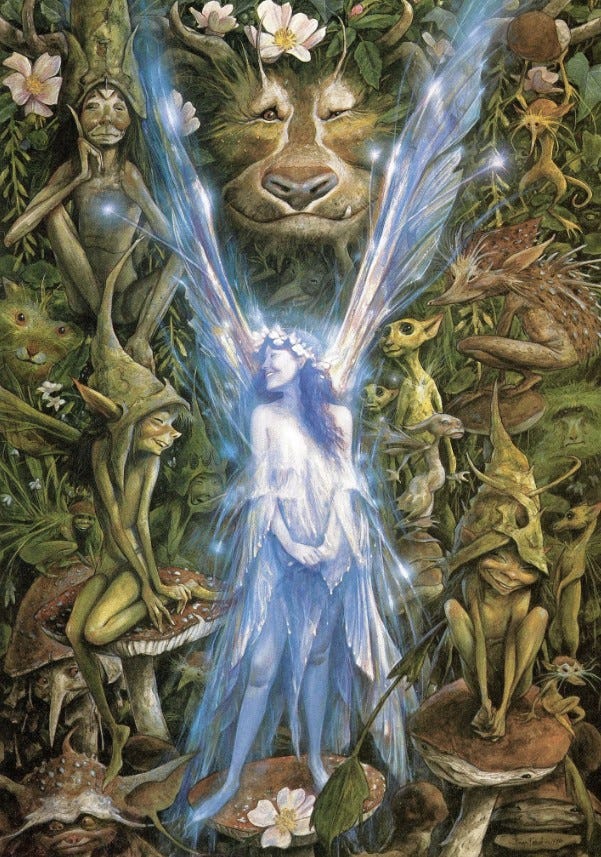

I am currently re-reading Brian Froud’s Good Faeries / Bad Faeries (a two-in-one exploration of the artist’s inspirations and fantastic worldbuilding). I read it many years ago when I was a child, but it is only upon re-reading it as an adult that I realised how much it influenced my perception of Faeries and the lands they inhabit. Froud’s Fae are captivating characters that dance the line between humanoid and animal. What I love most is how Froud’s so-called ‘Bad Faeries’ are no less beautiful and fascinating than their ‘Good’ counterparts. None of them, of course, neither Good nor Bad, are Black.

Amy Brown was another artist who influenced me personally, as well as my understanding of the world of the Faeries. I even have signed prints I received as a Christmas gift several years ago. Again, her work almost exclusively depicts white Faeries. Please don’t get me wrong, this isn’t intended to criticise these artists for their lack of diversity. I don’t know nearly enough about them or their personal views to make assumptions of their intentions. Instead I mean to tell a story of what I believe to be at best an unconscious bias and at worse a methodical practice of stereotyping in the literary, folkloric, and artistic worlds.

Black Faeries matter because they illustrate the fact that Black softness exists.

Blending fantasy with the realism of the Black experience

There have been many strides in media depictions of Black fantasy. Sinners, for exampled, pulled in over $300 million this year and stirred up simultaneous conversations about race in America and the global origins of the vampire mythos. I loved every second of the film, it must be said. I saw it in cinemas twice and plan to purchase the DVD as soon as possible.

However, I couldn’t help wondering if the correlation between Blackness and vampirism had some hand in the film’s accepta. Even Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a thinly-veiled depiction of Eurocentric fears of the other. Vampires have always represented that which we fear and yet find unquestionably alluring. So, too, has Blackness. They make an easy pairing in the current consumer consciousness.

Many media depictions of witches also align conveniently with the perpetuated stereotypes of Blackness—powerful and yet capable of great harm if allowed to lose control, cloaked in darkness, heathen and carnal knowledge, exoticism, etc. Gods/Goddesses are an interesting pillar of fantasy tropes, though they tend to be tethered to often tired explorations of the singular culture they belong to. Where does that leave multi-cultural representation then, I wonder. Black ghosts/spirits are often depictions of benevolent and servile Blackness. I think we can probably come to conclusions as to why that is (oh, the Bagger Vance of it all). Though, some outliers depict Black characters as vengeful ghosts, which I’d love to explore further another time.

For now, I will digress and return to the subject of Black Faeries.

Faeries are unique in that they represent a wide-range of human imagination and serve as a spiritual link between our world and various unexplained phenomenon. I studied the great seanachaí, Eddie Lenihan, W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, and many others when researching for my doctoral thesis and novel, so I can safely say I do believe in Faeries (I do, I do).

Despite their universal appeal to human nature, they are often only depicted one of two ways in popular media—either diminutive and charming or ethereal and deadly. They are also almost always depicted as white. I believe these compartmentalised and limiting depictions arose largely due to the opposing nature of Faeries themselves, since Faeries are so difficult to define. We humans prefer the easy-to-define. It helps us classify ourselves by defining what does not ‘belong’. Faeries can be so much more than a binary ‘good’ or ‘bad’, ‘light’ or ‘dark’. This lends a capacity for a multi-faceted characterisation that isn’t always afforded to Blackness or other people of colour. So, they were boxed up and shipped out as White™. This image was sold to the public via movies, books, and even art such as the beautiful images Mr. Brian Froud dreamed up.

When I originally questioned why there are so few Black Faeries, I assumed there was a disconnect between the bright, effervescent imagery of the Fae and the more sultry, hyper-sexualised stereotype of Black femininity (given that so many Faeries present as female). However, even in sexual and/or fetishised depictions, Faeries are still often depicted as white women. Which eventually led me to the conclusion that what Black Faeries actually represent is joyful agency. Since there are so few examples in media of joyful Black agency, softness, self-affirmation, playfulness, and all the other things Black Faeries would represent, they are left out of the fantasy entirely. When they do arrive, they may feel like an ill-fit or have to do twice the work of the other well-established images of white representations.

Perhaps you will cry foul. “Faeries come from Irish and English folklore!” You’d say. “To make them Black would be cultural appropriation.” To which I would ask you to define the Fae. Tell me what characterises the Bean Sí or the Púca that insists they must be white? Define the Fae, if you can, and take your own time to research (I did my four years of it) creatures like the nymphs, dryads, djinn, mami wata, devas, silvane, gremlins, yōkai, aziza. Similarly, define a spirit, a demon, an angel, a god and try not to define the Fae. Faeries embody the very mutable fabric of folklore, which itself has no borders and spans the confines of time and language. Faeries shapeshift (literally and figuratively) to reflect the many universal experiences of humans. It is only humans who seek to hem them in.

We need more Black Faeries in our stories, on our screens. We need more Black Faeries because if we can finally allow ourselves to free these creatures from the limitations we impose upon them, perhaps we can also free ourselves of the same narrow cages.